Teaching my first course - Intro to Cognitive Neuroscience!

I got to teach my first college-level course for students!! I created my own class — in which I taught Cognitive Neuroscience! — and I taught a group that all identified as low-income and/or first-generation college students through the Upward Bound Math Science (UBMS) program. During these two weeks, I also wanted to do a bit more than just expose students to the wonders of the brain and behavior; I wanted to see if I could inspire them to envision for themselves a career in science.

Background

Details Regarding Introduction to Cognitive Neuroscience Class

I taught a one-week introductory cognitive neuroscience course twice. Of course, there is no way that I can teach a full semester’s worth of content – which was never the goal! Instead, I aimed to expose them to enough content that would motivate them to study more in college (if they so chose!). Or, at the very least, know that this field exists as an academic option for them (fun fact! I did not know this was a field until I arrived at college; I just thought cog neuro and psychology were the same thing).

With all this in mind, and given how many students wanted to take the class, I dedicated each day to a particular lobe of the brain. I started with the frontal lobe (a personal favorite), then the parietal (personally, a difficult lecture), followed by the temporal lobe (one that I am biased towards as well due to my research interests), and finally we ended with a lecture on the occipital lobe (not the most engaging one for a 3-hour lecture – but we made it work!). Essentially, each lecture described the overall function of each lobe with very, very little details about structure. This was mixed in with various research and patient studies, interactive activities, and some suprisingly electrifying disucssions. For example, the first day, we talked about “neurolaw” and debated the following 1:

Imagine you are an attorney and you hear of a case regarding a man who physically assaulted their wife which resulted in her being in a coma. The man was reported by police to be extremely hostile, swearing constantly, and extremely erratic. At the hospital, friends point out that this person’s behavior was sudden and bizarre; they were a kind person before who never acted violently — especially with their partner. Doctors perform an MRI and find a large — but operable — brain tumor on the frontal lobe of the brain. After the surgery, the patient returns to “normal” and is mortified and extremely remorseful for what they did. Is this person guilty? Why or why not?

Data Collection

After each lesson, I asked students to complete a post-class survey as a way to acquire feedback on the topic of the day, to evaluate my abilities as a lecturer, and to explicitly comment on what they liked and what changes they recommended to improve their learning. I also wanted to gauge their comfort with the class discussions; because I was not sure what level each student was, I wanted to be mindful of some students who may not have felt comfortable engaging in discussion — and more importantly, wanted to figure out if I could help include those students. Additionally, on some days, we did some interactive activities (that I sometimes came up with 20 minutes before class started) and wanted feedback on if the activity helped reinforced their learning / anything at all. Results from these daily surveys are described in the data section.

In addition, I also administered a pre- and post-course survey to evaluate how this class affected their self-perception as a scientist. More on that in the next section.

Empowering STEM Identity

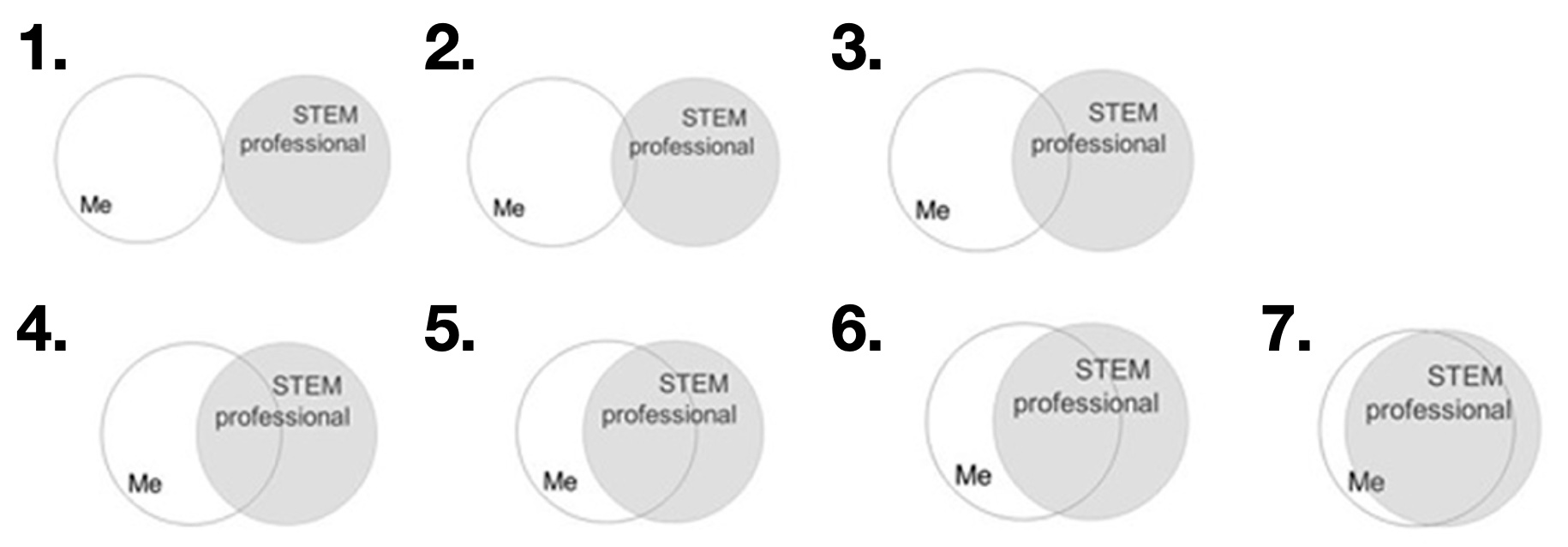

Prior to designing the course, I found an article by McDonald et al. (2019) that provided a quick assessment of someone’s identity as a science, technology, mathematics, and engineering (STEM) professional. An image of what they is provided in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: STEM POI Image

Essentially, students were to look at the image and select the one that best resembles how much they feel their personal identity intersects with a STEM one (for example: if I were to answer this question using the image above as a framework, I would select ‘7’ as my response, as I feel that being a STEM professional fully aligns with my personal identity). I wanted to gauge how students perceived themselves at the start of the class and whether this changed by the end of the week 2.

While the paper that introduced provides some evidence that the single-assessment was sufficient to portray someone’s STEM elements, I did want to also include another battery that they referenced. Specifically, I wanted to use a set of questions from Young et al. (2013), as it incorporated 9 additional questions to ascertain one’s proclivity to associate with STEM characteristics. However, I wanted to include a question of my own (Question 10) to acquire some future aspirations details. The following questions that were surveyed are as follows:

- Being a STEM student is an important reflection of who I currently am

- In general, being a STEM student is an important part of my current self-image

- Being a STEM student is important to my sense of what kind of person I am now

- Overall, being a STEM student has very little to do with how I feel about myself

- It is not important to me to be good at STEM

- I very much like doing STEM

- I would take more STEM classes even if I didn’t have to

- In general, I find working on STEM assignments very interesting

- I spent time on STEM work because I have to

- I envision myself becoming a STEM professional (e.g., doctor, researcher, etc.)

Students were to respond to each question on a 5-point likert scale (where 1 was ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 being ‘Strongly agree’). For each respondent, I then calculated a STEM Score: adding the value provided from the STEM-PIO with all of the responses from the 10-questionnaire. However, I reverse coded 3 responses — Questions 4, 5, and 9 — as these were incorporated to ensure students were carefully reading each statement (and not just selecting ‘Strongly agree’ on each question).

Now on to the fun part — the results!

The Data

Course Feedback

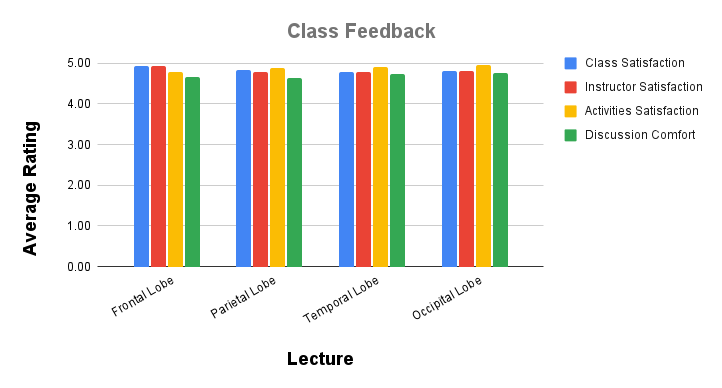

First, reviews for my class were overwhelmingly positive (🥲). Figure 2 and Table 1 provides an overview of the scores provided.

Figure 2: Class Feedback by Topic

Table 1

| Lecture | Class Satisfaction | Instructor Satisfaction | Activities Satisfaction | Discussion Comfort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal Lobe | 4.94 | 4.94 | 4.78 | 4.67 |

| Parietal Lobe | 4.84 | 4.79 | 4.89 | 4.63 |

| Temporal Lobe | 4.78 | 4.78 | 4.91 | 4.73 |

| Occipital Lobe | 4.81 | 4.81 | 4.95 | 4.75 |

| Overall | 4.84 | 4.83 | 4.88 | 4.69 |

Personally, the scores for the class were

Shift in STEM Identity

For these two weeks, what I wanted to test was how exposure to cognitive neuroscience (i.e., topics rarely taught to students in New Mexico) would impact their self-perception of their science identity. Table 2 below provides summary statistics using the STEM Scores calculated from their pre and post responses.

Table 2

| Pre-Score | Post-Score | Difference Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 26 | 20 | -6 |

| max | 47 | 49 | 13 |

| mean | 34.5 | 37.27777778 | 2.777777778 |

| sd | 6.373197554 | 7.061124353 | 5.116933314 |

When reviewing this data, I paid close attention to the Difference Score (the change between the Pre and Post Scores).

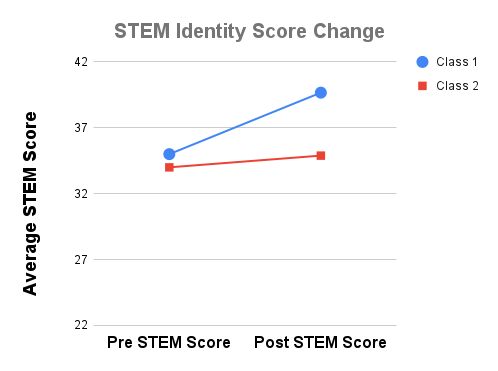

However, I wanted to narrow down the data a bit more and observed something interesting. Figure 3 below provides a graph that distinguishes the differences between the two classes.

Figure 3: STEM POI Change by Class Week

It’s quite clear that the sharpest difference was observed in Class 1 with almost very little change in my second class. Table 3 provides specific data to further showcase that difference.

Table 3

| Pre STEM Score | Post STEM Score | Average Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 35 | 39.66666667 | 4.666666667 |

| Class 2 | 34 | 34.88888889 | 0.8888888889 |

| All students | 34.5 | 37.27777778 | 2.777777778 |

On average, students in Class 1 had almost a 5-point difference on their STEM scores; on the other hand, students in Class 2 barely achieved an average of a 1-point difference.

Interestingly, class satisfaction ratings did not reflect similar differences; students in both classes seemed to equally enjoy the materials. So where was this coming from?

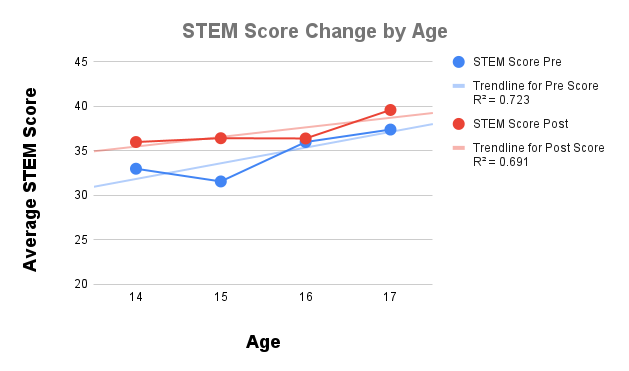

A potential (albeit, weak) possibility is differences in age. This is illustrated in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: STEM POI Change by Age

First, almost every student in my cognitive neuroscience class the first week were either age 16 or 17. In my second week, they were mostly 14 and 15. From Figure 4, it appears that as students get older, so does their STEM identity score — with regards to both the pre and post scores. So it is possible that age can be a factor such that, as they get older (and closer to college admissions), so does how they perceive themselves as budding scientists.

The answers to the aforementioned questions are complicated to answer because (a) I did not have enough students and (b) did not acquire sufficient data to test different possibilities. A third point, (c), is that this was not a randomized control trial; there’s no way to determine whether or not my actual instruction made an impact on their STEM identity since students opted into my course.

Short Reflection

In my short adult life, I have done many difficult things: I lived in the mountains for three weeks and nearly fell off one; after I graduated, I had to make friends in a foreign city during a time period where it is difficult to make new companions; I told my boyfriend two months into our relationship that I loved him; and I created and taught my own cognitive neuroscience class — which was was arguably the hardest thing I’ve done so far. Here’s why.

First, it should come to no surprise that learning and teaching are two different endeavors, and after these two weeks I’m not entirely sure one informs the other: I’d like to believe that I am really good at the former, but that does not necessarily mean it translates to the latter. Part of that is because teaching is extremely multi-faceted. The best analogy I can come up with to capture this sentiment is to imagine an athlete. Someone may be very good at a particular sport — like soccer! — but being good at soccer does not innately make someone a good soccer coach; they work different muscles. In fact, this week I learned that what made me a good teacher had nothing explicit to do with my intelligence or knowledge of my field but instead other dimensions completely separate to my science identity: my personality. This is the second insight I made from this experience.

When I reviewed the feedback from the students, I got many responses that highlighted aspects of my personality that made the class exciting (take that, middle school bullies!). For example, several students mentioned an appreciation for my “infectious energy.” Which is true on two parts: I feel most powerful when I am doing cognitive neuroscience research — and am at my most comfortable when I am surrounded by people similar to me. In fact, I was evaluated by an experienced teacher who provided some wonderful feedback. One aspect that made me feel particularly giddy was a comment on when I asked the class if they wanted a 5 or 10-minute break. The students picked 5, and the comment the observer made was this:

How often when high school students are asked if they would like a short break or a long break do they pick the shorter break? Your class is that good.

Lastly, I have come to understand that while I look forward to teaching and mentoring, this experience taught me that what I loved most of all is cognitive neuroscience and research. It was absolutely thrilling to share my love for science with other students — and it was even more refreshing to hear from them how that came across each and every day. I am not quite sure this experience was sufficient to make me a good teacher; I think I need more formal pedagogical training if I wanted to accomplish such a goal. However, it did make me excited to improve as a researcher and eager for another opportunity where I am able to give a science talk to another group of students.

Notes

-

Before any zealous neuroscientists comes for me on this discussion post: know that the goal was not the scientific accuracy in the prompt! It was instead a conversation starter to get them to think critical about the limits — or potential — of neuroscience research to inform real-world settings beyond the lab. It was meant as a way to help students figure out which area of neuroscience could interest them rather than to determine the legal merits of this prompt. ↩

-

Was not an RCT but would be fun to consider something similar in the future! ↩

Leave a comment